4. The Incident Response Lifecycle¶

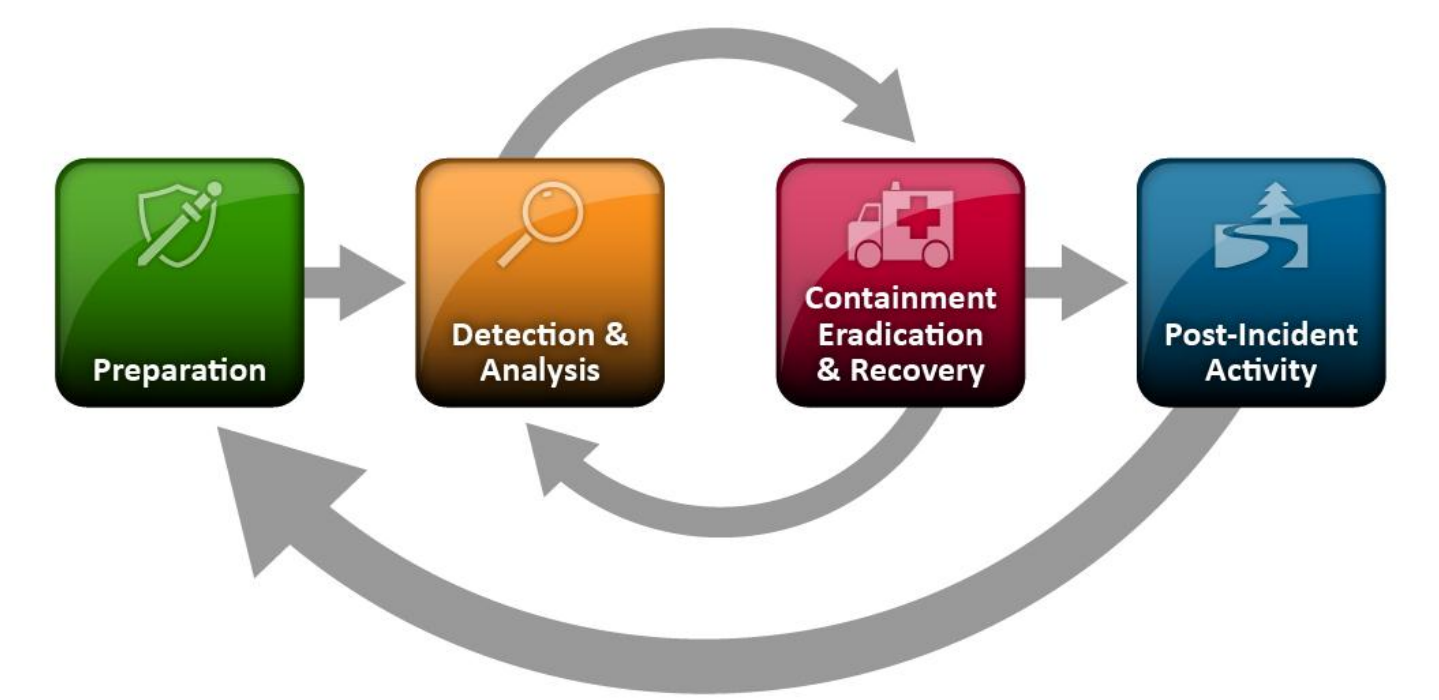

The phases of the incident response process are preparation, detection and analysis, containment, eradication and recovery, and post-incident activity.

The preparation phase of the process involves establishing and training an incident response team, and acquiring the necessary tools and resources. During preparation, the organization applies security controls that are selected based on the results of risk assessments in order to limit the number of incidents that will occur. Since risks are persistent and constantly changing, incidents can occur despite the application of controls. Detection of security breaches is necessary to alert the organization whenever incidents occur. Depending upon the severity of the incident, the organization can mitigate the impact of the incident by containing it and ultimately recovering from it. During this phase, incident response activity often goes back to the detection and analysis phase to see if additional hosts have been affected by the security incident.

After the incident is adequately handled, the organization issues a report that details the cause and cost of the incident and the steps the organization should take to prevent future incidents.

4.1. Preparation¶

Improve Organizational Readiness; Having a clear plan and being prepared for an incident will decrease dwell times and improve overall security.

4.1.1. Appoint Team Members¶

The Critical Incident Response Team (CIRT) should be made up of several people that consist of different disciplines to handle the various problems that could arise during an incident.

Critical Incident Response Teams often include:

IT

Legal

Compliance

Audit

Privacy

Marketing

HR

Senior executive

4.1.2. Policy¶

A policy provides a written set of principles, rules, or practices within an organization; it is one of the keystone elements that provide guidance as to whether an incident has occurred in an organization.

Policy typically includes:

Statement of management commitment

Purpose and objectives of the policy

Scope of the policy (to whom and what it applies and under what circumstances)

Definition of computer security incidents and related terms

Organizational structure and definition of roles, responsibilities, and levels of authority; should include the authority of the incident response team to confiscate or disconnect equipment and to monitor suspicious activity, the requirements for reporting certain types of incidents, the requirements and guidelines for external communications and information sharing (e.g., what can be shared with whom, when, and over what channels), and the handoff and escalation points in the incident management process

Prioritization or severity ratings of incidents

Performance measures

Reporting and contact forms

4.1.3. Response Plan/Strategy¶

Organizations should have a formal, focused, and coordinated approach to responding to incidents, including an incident response plan that provides the roadmap for implementing the incident response capability. Each organization needs a plan that meets its unique requirements, which relates to the organization’s mission, size, structure, and functions. The plan should lay out the necessary resources and management support.

The incident response plan should include the following elements:

Mission

Strategies and goals

Senior management approval

Organizational approach to incident response

How the incident response team will communicate with the rest of the organization and with other organizations

Metrics for measuring the incident response capability and its effectiveness

Roadmap for maturing the incident response capability

How the program fits into the overall organization

Develop processes to be followed by incident type

Example response plans can be downloaded Here

4.1.4. Communication¶

Each member of the incident response team should have clear instructions on who to contact in case of an incident.

- Communication plan should include:

Contact information for team members and others within and outside the organization (primary and backup contacts). Information may include phone numbers, email addresses, and instructions for verifying the contact’s identity

On-call information for other teams within the organization, including escalation information

The contacts should include who and when it is appropriate to contact them and why

Issue tracking system for tracking incident information, status, etc.

When to include law enforcement during an incident.

4.1.5. Documentation¶

Incident Response Teams should have the following documentation on hand to reference during an incident investigation.

Port lists, including commonly used ports and Trojan horse ports

Documentation for OSs, applications, protocols, and intrusion detection and antivirus products

Network diagrams and lists of critical assets, such as database servers

Current baselines of expected network, system, and application activity

During an incident investigation it is important to document all actions that were performed (e.g. commands typed, systems affected, containment strategy, etc).

Documentation should be able to answer the Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How questions should they ever arise; without such information one could leave a sense of uncertainty if something was called into question.

Documentation should contain information on the following:

The current status of the incident (new, open, in progress, pending, false positive, closed)

A summary of the incident

Indicators related to the incident

Other incidents related to this incident

Actions taken by all incident handlers on this incident

Chain of custody, if applicable

Impact assessments related to the incident

Contact information for other involved parties (e.g., system owners, system administrators)

A list of evidence gathered during the incident investigation

Comments from incident handlers

Next steps to be taken (e.g., rebuild the host, upgrade an application)

In addition, this documentation can be used for Post-Incident review to improve efficiency by creating additional response plans.

4.1.6. Training¶

User Awareness and Training. Users should be made aware of policies and procedures regarding appropriate use of networks, systems, and applications. Applicable lessons learned from previous incidents should also be shared with users so they can see how their actions could affect the organization. Improving user awareness regarding incidents should reduce the frequency of incidents. IT staff should be trained so that they can maintain their networks, systems, and applications in accordance with the organization’s security standards.

4.2. Detection & Analysis¶

Incidents can occur in countless ways, so it is infeasible to develop step-by-step instructions for handling every incident. Organizations should be generally prepared to handle any incident but should focus on being prepared to handle incidents that use common attack vectors. Different types of incidents merit different response strategies.The attack vectors listed below are not intended to provide definitive classification for incidents; rather, they simply list common methods of attack, which can be used as a basis for defining more specific handling procedures.

External/Removable Media

Denial of Service/Brute Force

Malicious HTTP Activity

Impersonation

Improper Usage

Loss or Theft of Equipment

4.2.1. Detection¶

HAWK will be the main source of identifying incidents. Using combination of HAWK’s analytics and HAWK’s IDS systems, events will be analyzed and prioritized showing which Security Incidents should be reviewed. Other incidents can come from users reporting their computer is acting strangely, or finding USB drives in public.

HAWK Incident Manager will show the prioritize security incidents to review.

4.2.2. Analysis¶

The following are recommendations for performing the initial analysis and validation easier and more effective:

Maintain and Use a Knowledge Base of Information – The knowledge base should include information that analyst need for referencing quickly during incident analysis. Although it is possible to build a knowledge base with a complex structure, a simple approach can be effective. Text documents, spreadsheets, and relatively simple databases provide effective, flexible, and searchable mechanisms for sharing data among team members. The knowledge base should also contain a variety of information, including explanations of the significance and validity of precursors and indicators, such as IDS alerts, operating system log entries, and application error codes.

Use Internet Search Engines for Research – Internet search engines can help analysts find information on unusual activity. For example, an analyst may see some HAWK IDS events searching for the vendor ID may return some hits that contain logs of similar activity or even an explanation of the significance of the IDS Rule.

HAWK IDS Event(s) – If the Incident consist of IDS Events, The alert name and vendor id should be used for searching the Internet for additional information.

System Event Log(s) – If the Incident consist of syslog events, If the vendor ID is supplied searching the vendors documentation typically will give an explanation on what would cause the event to occur. If the vendor ID isn’t supplied typically reading the information on the Payload and Analytics tab of the event will be enough information to determine what caused the event to occur.

Assign Appropriate Team Members – After the initial analysis, the analyst should bring in the appropriate team members that have more in-depth knowledge about the asset to verify the security incident. If verified to be a security incident, this team member should be involved in the Containment, Eradication, & Recovery processes.

Evaluate precursors and indicators – Related Incidents on the Summary page should be reviewed to realize the full scope of an incident. In addition the HAWK’s Operations Dashboard can be used to search for similar incidents (i.e. By resource, port number, alert name)

Track incidents and maintain documentation – Each incident should be tracked and documentation should be maintained using the documentation steps outlined in preparation.

Incident Prioritization – Prioritizing the handling of the incident is perhaps the most critical decision point in the incident handling process. Incidents should not be handled on a first-come, first-served basis as a result of resource limitations. Instead, handling should be prioritized based on the relevant factors, such as Functional Impact, Information Impact, and Recoverability of the incident. HAWK will prioritize incidents based on assigned criticality and analytics. However, an analyst may feel that another incident has higher priority based on updated or new knowledge.

4.3. Containment, Eradication, & Recovery¶

4.3.1. Containment¶

Containment is important before an incident overwhelms resources or increases damage. Most incidents require containment, so that is an important consideration early in the course of handling each incident. Containment provides time for developing a tailored remediation strategy. An essential part of containment is decision-making (e.g., shut down a system, disconnect it from a network, disable certain functions). Such decisions are much easier to make if there are predetermined strategies and procedures for containing the incident. Organizations should define acceptable risks in dealing with incidents and develop strategies accordingly.

Containment strategies vary based on the type of incident. For example, the strategy for containing an email-borne malware infection is quite different from that of a network-based DDoS attack. Organizations should create separate containment strategies for each major incident type, with criteria documented clearly to facilitate decision-making.

Criteria for determining the appropriate strategy include:

Potential damage to and theft of resources

Need for evidence preservation (e.g., Is necessary to perform a system backup before wiping and re-imaging the system to preserve evidence)

Service availability (e.g., network connectivity, services provided to external parties)

Time and resources needed to implement the strategy

Effectiveness of the strategy (e.g., partial containment, full containment)

Duration of the solution (e.g., emergency workaround to be removed in four hours, temporary workaround to be removed in two weeks, permanent solution)

Isolate a network segment of infected workstations

Taking down production servers that were compromised and having all traffic routed to failover servers

Temporary fix in order to allow the asset to continue to be used in production.

Installing security patches.

4.3.2. Eradication¶

After an incident has been contained, eradication may be necessary to eliminate components of the incident, such as deleting malware and disabling breached user accounts, as well as identifying and mitigating all vulnerabilities that were exploited. During eradication, it is important to identify all affected hosts within the organization so that they can be remediated. For some incidents, eradication is either not necessary or is performed during recovery.

4.3.3. Recovery¶

The purpose of this phase is to restore systems to normal operation, confirm that the systems are functioning normally, and (if applicable) remediate vulnerabilities to prevent similar incidents. Recovery may involve such actions as restoring systems from clean backups, rebuilding systems from scratch, replacing compromised files with clean versions, installing patches, changing passwords, and tightening network perimeter security (e.g., firewall rulesets, boundary router access control lists). Higher levels of system logging or network monitoring are often part of the recovery process. Once a resource is successfully attacked, it is often attacked again, or other resources within the organization are attacked in a similar manner.

It is essential to test, monitor, and validate the systems that are being put back into production to verify that they are not being reinfected by Malware or compromised by some other means.

- Some of the important decisions to make during this phase are:

Time and date to restore operations – it is vital to have the system operators/owners make the final decision based upon the advice of the CIRT.

How to test and verify that the compromised systems are clean and fully functional.

The duration of monitoring to observe for abnormal behaviors.

The tools to test, monitor, and validate system behavior.

Eradication and recovery should be done in a phased approach so that remediation steps are prioritized. For large-scale incidents, recovery may take months; the intent of the early phases should be to increase the overall security with relatively quick (days to weeks) high value changes to prevent future incidents. The later phases should focus on longer-term changes (e.g., infrastructure changes) and ongoing work to keep the enterprise as secure as possible.

4.4. Post-Incident Activity¶

One of the most important parts of incident response is also the most often omitted: learning and improving. Each incident response team should evolve to reflect new threats, improved technology, and lessons learned. Holding a “lessons learned” meeting with all involved parties after a major incident, and optionally periodically after lesser incidents as resources permit, can be extremely helpful in improving security measures and the incident handling process itself. Multiple incidents can be covered in a single lessons learned meeting. This meeting provides a chance to achieve closure with respect to an incident by reviewing what occurred, what was done to intervene, and how well intervention worked. The meeting should be held within several days of the end of the incident.

Questions to be answered in the meeting include:

Exactly what happened, and at what times?

How well did staff and management perform in dealing with the incident? Were the documented procedures followed? Were they adequate?

What information was needed sooner?

Were any steps or actions taken that might have inhibited the recovery?

What would the staff and management do differently the next time a similar incident occurs?

How could information sharing with other organizations have been improved?

What corrective actions can prevent similar incidents in the future?

What precursors or indicators should be watched for in the future to detect similar incidents?

What additional tools or resources are needed to detect, analyze, and mitigate future incidents?

Using the incident’s documentation and discussions from the “lessons learned” meeting, the items in preparation phase should be improved. (e.g., adjusting or adding response plans, requirements for documentation, update communication plan)

4.5. Additional Resources¶

Please review the following resources for a more in-depth review in creating a strong Critical Incident Response Team.